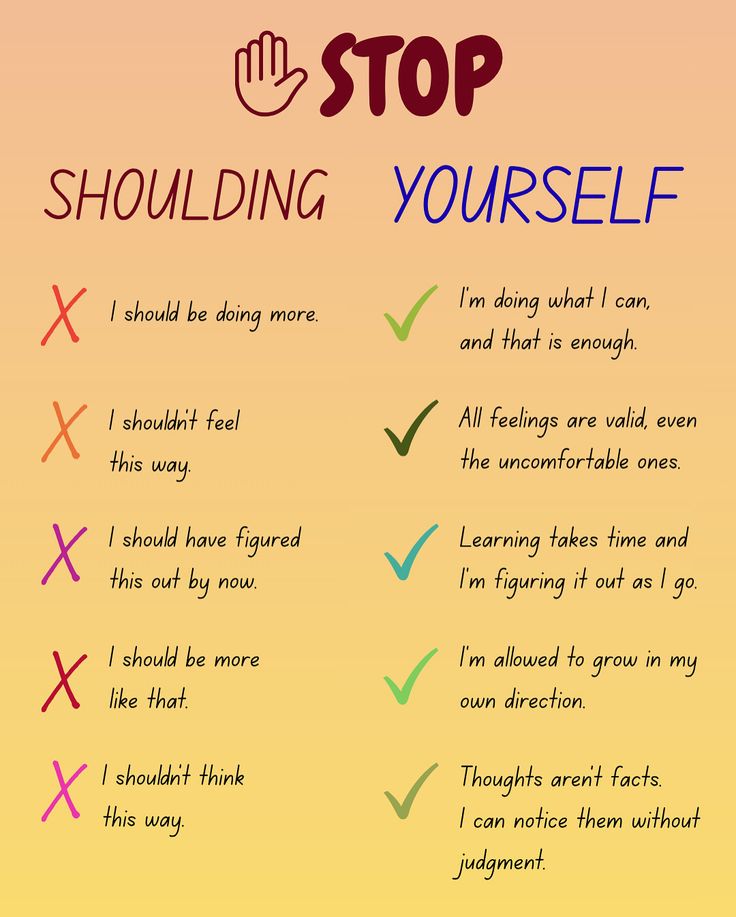

We as humans are fantastic at berating ourselves, shaming ourselves, calling ourselves derogatory names. Most of us are our own worst critics. Many of us speak negatively to ourselves, even with cruelty. Many of us say things to ourselves that we likely would never say to a friend or family member. Most of us are guilty of shoulding all over ourselves. It’s time to stop.

Yes, it’s time to stop shoulding yourself. And, yes, that sounds exactly the way it is supposed to. Many of us engage in the sort of thinking that tells us that we should be doing this, or should be doing that, that we should feel a certain way, think a certain way, look a certain way. We do this shoulding of ourselves with some weird hope that we may feel better about something in our lives, the way we exist in the world … that doing so will make us somehow worthy of love and belonging and acceptance.

The fact of the matter is, we cannot shame ourselves into feeling better, doing better, performing better, thinking differently or looking a different way. When we should ourselves, we likely are coming from a place of shame. For “should” is borne of shame. And that little gremlin shame likes to tell us that we are not good enough, that we are not smart enough, that we are not doing enough, that we are not enough of anything. That gremlin is wrong. We were born enough.

When we should ourselves we are not treating ourselves with the same compassion, respect or care that we likely offer to others. When we should ourselves, we are buying into the story that we are somehow, in some way, not good enough. It’s time to stop shoulding all over yourself.

So, how do we stop shoulding all over ourselves? We practice speaking kindly to ourselves. We practice offering ourselves some compassion. We practice caring for ourselves in healthy ways. We course correct and try to remind ourselves that we usually are doing the best we can with what we have right now. And we remind ourselves to test the veracity of our thoughts, look for evidence to the contrary and think of something positive, something helpful, to say to ourselves.

We stop shoulding all over ourselves by reminding ourselves that it is okay to be our own loudest cheerleader rather than our own loudest and meanest critic. Again, we cannot shame or should ourselves into being, thinking or feeling better. It just won’t work. What it will do is make us feel worse, and lead us into shame spiral that can feel hard to climb out of.

If you find yourself shoulding all over yourself, heading into that shame spiral, stop and think just for a moment if that line of thinking is helpful or hurtful. What evidence do you have to support those shoulding/shaming thoughts? Is there evidence to the contrary? Think about whether you would say or do to a friend or family member what you are saying or doing to yourself. Most likely, you would not speak cruelly or behave with cruelty toward a friend or family member. It is okay to be kind to yourself and to lift yourself up, particularly if you find yourself in a shame spiral.

It’s time to stop shoulding all over yourself. What steps might you be willing to take to move away from shoulding and shaming self-talk and behavior? Can you remind yourself that should is borne of shame and that shame tells us the lie that we are not good enough. Can you remind yourself that you are good enough exactly as you are?

~ Karri Christiansen, MSW, LCSW, CADC, CCTP